The 10 Most Influential Movies of the 21st Century

Musing Outloud about the New York Time's Top 100 Movies List

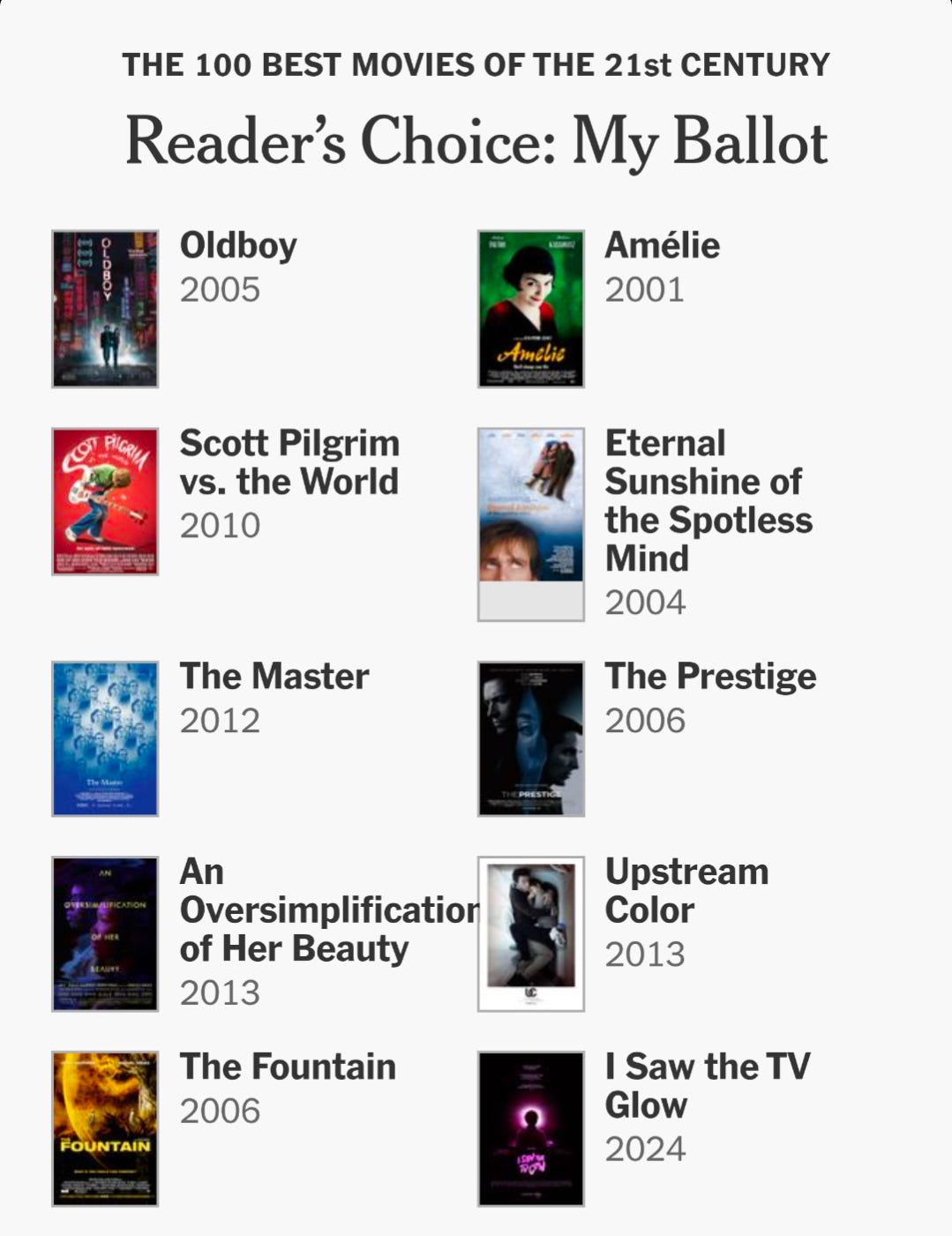

The NY Times released a list of the 100 Best Movies of the 21st Century . I haven’t seen it because I no longer have a subscription, but I was able to access their reader ballot and fill out a top-of-my-head list:

I did not put a lot of thought into the above ballot, just sticking to movies I know I’ve advocated for and will advocate for a long time, but I did have one regret two days later when I realized I forgot Tree of Life. I’m not gonna submit a new ballot, but I’d swap that one with The Master.

Anyway, “Best Movie” of the 21st century (soOoOooO FarRrrRrr) didn’t feel very enticing of a project to endeavor for. As I made my selections, I realized they are personal favorites that I enjoy watching a lot regardless of any faults or criticism and regardless of their influence or context within “the 21st Century”. I don’t really need them to be on a best list. They’ll always be my favorites in my own way.

That got me thinking. If we’re discussing “The 21st Century”, we’re not discussing “The Best.” We’re discussing what has affected the medium of film itself that has made it into the medium that it is in the 21st Century, as opposed to what the medium of filmmaking was in the 20th Century. Every one of the films on my list could have been made in the 20th Century technically, if not necessarily thematically or with the same narrative concerns and social context.

No, filmmaking has changed in the 21st century and in profound ways, and so here is a much different list. This is a list of movies I don’t necessarily advocate for seeing regardless of whether I like them. Some I love, some I like, some I merely respect, and one I haven’t even seen. But they have changed the face of filmmaking in a way that affects what audiences expect and frame what we think about when we think about what a movie is.

28 Days Later (2002) - Digital Cinema

I am nearing middle age, but the only two times I ever felt a distinct “generational” difference between me and people who were born after the year 2000 was once when I told some Zoomer colleagues of mine about what it was like dropping people off at the airport and actually walking them to the gate, and when I one day found myself telling some perplexed younger filmmakers how adamantly against “videotape” Hollywood used to be.

Before 28 Days Later came out, there were feature length movies that were shot on HD tape (HDV, “high definition video”). They were largely indie releases or cult experiences like The Blair Witch Project, or sometimes documentaries that would eke out a theatrical screening, but in general HDV was scorned as a “direct-to-video” tool, only useful for dirt cheap lesser quality products at Blockbuster. Not only did cinematographers, directors, producers, and studio heads all commonly announce, “Videocameras will never offer a high enough quality to present the real cinematic experience in a movie theatre!” but I even witnessed scrappy zero-budget penny pincher Lloyd Kaufman solemnly tell a group of film students during a Q&A that Troma only shoots on film because “video” is too low quality.

I was a burgeoning filmmaker back then, making my first forays into networking. Even little indie production companies in Albuquerque, NM sweated about how they could ever scrap together a budget for actual film because the miniDV cams they owned were strictly for industrial work.

Then 28 Days Later burst through the back curtain and announced to the world that these newfangled “camcorders” could make a product that could project on a big screen, and audiences wouldn't reject it screaming, “This isn’t a movie, it’s a video!”

Film use has cratered ever since.

HDV fed a 720i image onto an about 40min reel of magnetic tape, but it was quickly replaced by 1080p cams that wrote about 20min of footage to thick, heavy, and expensive solid state harddrives, which iterated higher in resolution and storage space and smaller in form factor until these days we’re swimming in prosumer 6K cameras that record over two hours of footage to 516gb SD cards that cost a tenth of what 516gb spinning disk harddrives cost about ten years ago.

Now film is a premium product for a specific theatrical experience, IMAX and 75mm and so forth. Everything else is digital cinema. “Video” is what someone posts on the Internet, instead of an actual reel of electronic tape that transmitted to “televisions.”

Now, if 28 Days Later didn’t come along, some other movie would have. But since 28 Days Later was the one that sold Hollywood on the premise of HDV, it also set the standards of the look for a good decade to come. The Aughts were full of overcranked, overcovered, undersaturated images essentially until the Canon 5D’s color science taught indie filmmakers that blacks could be deep and colors could be saturated, and later flat and raw files became technically accessible and color grading had a comeback.

I would even argue that a lot of digital’s ‘desaturated’ quality is less technical and more just reflex, even to the point of affecting the looks of things like the ostensibly colorful Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Lord of the Rings (2001-2003) / Raimi’s Spider-Man (2002-2007) trilogy — Multi-Episode Contracts

These selections are a little into the weeds, but essentially these two early Aughts trilogies expanded Hollywood’s idea of how they could contract movies. Both Lord of the Rings and Spider-Man had unusual production agreements for the time.

Peter Jackson pitched New Line, and New Line took a huge risk, on producing all three Lord of the Rings episodes at the same time in order to cut down on production costs. I can’t speak to Peter Jackson’s mindset, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he was fretting about being able to finish the series considering previous attempts never pulled through. It would have been awful to have to stop after The Fellowship of the Ring, even in some cases with it being profitable. New Line, on the other side, would have to have dealt with a huge loss if not only The Fellowship of the Ring flopped, but the flop cost three whole movies.

Spiderman was somewhat the reverse. The studio wanted to lock Sam Raimi, Tobey Maguire, and Kirsten Dunst into a three-picture deal in advance, seeing the burgeoning success of superhero movies and the concept of ‘trilogies’ in general, from Back to the Future through The Matrix (both of which had first movie successes and then received two sequel contracts). The risk was all on the creative’s side to be able to deliver all three movies, which turned out to make Spider-Man 3 a messy and combative work environment.

The reason both matter is that they were wildly successful. Audiences ate them up and proved that the studios could contain costs and plan in advance on multiple film roll-outs, reduce the rounds of negotiations with directors and actors trying to raise rates between sequels, and it helped marketing when the audiences knew to anticipate new episodes.

Pretty much immediately, Christopher Nolan was signed by Warner Bros to produce a Batman trilogy and Kevin Feige approached Disney with an idea of how they could help Marvel studios… (see The Avengers, below).

Avatar (2009) — Virtualized Cinema and the DCP

Almost exactly ten years after The Matrix, James Cameron said, “you know, plugging in to virtual networks is actually cool and eco friendly and spiritual” and the world said, “Yes absolutely here’s literally billions of dollars thank you”.

Avatar is currently the top-grossing movie of all time, earning $2.9billion worldwide, so we could argue it’s ‘influential’ because it’s cinema’s current largest financial success, and if we wanted to be populist about it we could argue that it’s influential because billions of people have seen it and liked it and so therefore it has ‘influenced’ so many imaginations.

Sure. I also for the life of me can’t remember a single line of dialog or really much of what happened. Backlash was pretty harsh against the actual qualities of the story, which I won’t beat up on, but which I wouldn’t say necessarily influenced how stories are told in movies in the 21st Century.

No, Avatar changed the workflow of digital cinema entirely and ushered in new production and distribution modes. Most of its billion-dollar budget was actually research and development of new camera hardware and software that would enable things like camera movement-matching on virtual green screens, pre-rendered 3D real-time compositing, polarized stereoscopic 3D, and digital projection.

After Avatar’s success came a flood of “3D movies” which sometimes had the premium sell of having been shot on “Avatar’s camera technology” (I remember this being actual trailer copy for a Resident Evil film) or was just simply processed to be 3D from a 2D image in post-production. This 3D period did not last much longer than Hollywood’s previous few attempts at making 3D a thing. It’s still around, but the premium theatrical experience has sought “immersion” in a variety of different ways.

But what Avatar did irrevocably was force movie theatres worldwide to tear out their film projection platters and replace them with digital projectors. DCP standards set in 2005 started rolling out and taking over most of how workflow is considered from camera card to projectable file.

Meanwhile, Avatar set off debates about whether it was really a ‘live action movie’ if so much of it was CG designed characters running around CG worlds, basically expanding the mo-cap character animation of Lord of the Rings to entire sequences and worlds. A year later, Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland comes out and Disney starts its series of “live action” animated updates of their hand-drawn animated classics. The line between live action and animated feature was blurred and never really redefined since.

This was also when Hollywood learned that shooting on virtual locations is so much less of a hassle than shooting in real locations, where you have to deal with, like, locals, customs, and location managing. Without Avatar we don’t have The Mandalorian, which managed to stay in production through the COVID pandemic because it was shot entirely on virtual sets.

Hollywood tasted virtual reality and loved it. And the concept expanded beyond the interests of techny nerds like James Cameron but to Hollywood’s relationship with the tech industry itself (See Her, below).

The Avengers (2012) — Cinematic Universes

At one point in the Aughts, a man named Kevin Feige went to Disney and made a pitch: Marvel Studios was struggling, but superhero movies were taking off. If Disney could provide the capital for some high-production value films, it could buy Marvel Studios and have access to nearly a century’s worth of already written characters and stories with a built-in fan-base.

Disney and Marvel were not to sure, so Feige asked to produce Iron Man (2008), in the hopes that he could prove the strategy off of a character that wasn’t as set in Hollywood film lore as a character like Spider-Man, Batman, or Superman. Other than those three characters, superheroes in Hollywood weren’t considered broadly successful and usually only stuck around if they had a cult following.

Iron Man was a huge success, and Disney and Marvel extended the deal to produce the rest of the Avengers team’s character movies, resulting in Disney purchasing Marvel Studios by the end of 2009.

Movie by movie, Feige built the steps to 2012’s The Avengers, a masterstroke of corporate synergy and IP management that gave superhero nerds everything they ever wanted and caused them and Disney alike to chase that high ever since. The Avengers rolled out “the Marvel Cinematic Universe.”

It’s success was quickly followed by Hollywood’s attempt to build additional cinematic universes. Warner Bros looked at what they had with Nolan’s Batman trilogy and went looking for people to produce a “DCU.” Series such as Transformers and Mission: Impossible dropped the numbers from their sequel titles. Post-credit roll scenes proliferated. Actors started getting cast as a character for many movies, not as a specific character for specific movies.

Disney itself followed up The Avengers by purchasing Lucasfilm from George Lucas in 2012, under the assumption that the Star Wars phenomenon was the same as the MCU phenomenon. Spoiler alert: they are not the same phenomenon. Now, as audiences are experiencing superhero fatigue and so many “cinematic universes” ended up becoming messy and burdensome to manage across so many directors and aging actors, there lies an open question of whether the structure will fall apart.

However, Disney’s expansion into Disney+ has given ‘cinematic’ universes new life in extended and limited television series alike, and the overall movies are still profitable, while the merchandising and other IP benefits continue churning money.

I don’t think this will necessarily end, but I think “cinematic” theatrically-released episodic work is going to learn a lot from televised home streaming episodic work in terms of having showrunner-style producers who manage the universes’ continuity and adapt them to audiences tastes while keeping dependencies on specific above-the-line talent to a minimum.

This is one reason why Hollywood is drooling over AI generated imagery. If they can have Wolverine without depending on Hugh Jackman, Iron Man without Robert Downey Jr., and not have to sort out the differences between managing someone like Sam Raimi and someone like James Gunn, they’ll truly encapsulate “IP value” in its most Platonic form.

Her (2013) — The Merger of Hollywood and Silicon Valley

Certainly I could make the case that Avatar was the merger between Hollywood and Silicon Valley, with its embrace of digital technology and virtualized filmmaking. It even adopted Silicon Valley’s techno-critical aspects about “extractive” versus “data” industries. It’s all good to plug in to wear digital blue-face and commune with the global network, as long as you’re not ruining Nature™. Code should eat the world, but shame on you for oil production.

But Her was the point when the medium of film started selling the world Silicon Valley’s foundational stories. It’s important that it wasn’t even a studio film but rather a studio indie. Her aestheticized where Silicon Valley was going using Silicon Valley’s own logic, rational, and point of view. Her was when Hollywood became the official propaganda arm of Silicon Valley.

Director Spike Jonze, I suspect, would disagree. He shares with Dave Eggars that, “But behind the irony it’s all very human, right? That’s the double-irony, ironically” nonsense Gen X cursed us with, leaving us with an ‘open ending’ where the nature of Theodor and Samantha’s relationship is offered to audience to discuss and determine; but no, functionally this movie was a Kurzweillian fever dream set up to make us accept the premise even if we disagreed with the conclusion. The overall implied acceptance not “of our relationship to devices” but how would we maintain intimate relationships with our technology manufactured consent to Silicon Valley to go about engineering UX with these relationships in mind. Hence ChatGPT.

This is very different than 20th Century sci fi about our potential for relationships with android robots. For one thing, the devices are already here; for another thing, the relationship is framed as natural and grows organically, instead of being designed.

This movie is probably the least watched and will be the least likely one to ‘stand the test of time’ of all of them on this list; and, because my argument is about its content rather than its technical influences, it’s a bit more difficult to lay objective claims about its influence on culture. However, it was the big breakout movie hit in which Silicon Valley was no longer ‘the tech industry’ but rather our American social hegemony. It was no longer “what we’re inventing” but “who we are,” “where we’re going” but “where we’ve arrived.”

It doesn’t matter if Theodor was left staring at the sky, wondering if Samantha was ever there. We’ve been trying to find a way out of her/Her’s world ever since.

Ex Machina (2014) — “An A24 Film”

I do not remember when I first heard someone say, “Hey, have you seen the new A24 film?” but the rapid adoption of that phrase was stunning. “A24” went from being an easily missable quick chromatic-split before a couple-few indie films to being a logo custom-embedded into trailers of its movies to make clear we knew: this is an A24 movie.

I hardly had time to wrap my mind around it before there was an “A24 look,” A24 merch store, A24 fans, and turgid backlash articles from grumpy cranks about movies being A24ified.

The only comparable brand loyalty I’ve seen to A24 as an umbrella is “Disney kids,” but that feels different. When I first discovered Kubrick, I discovered that most of his movies were released by Warner Bros, and I thought that was a really interesting studio / director relationship, but it never inspired me to become a Warner Brothers loyalist. A24 fandom is akin to someone saying, “I’ll watch any movie that is released by Warner Bros because Warner Bros released Kubrick films” rather than “I like the overall experience of princesses and rides and music and enchantments” that Disney addicts jones for. “Disney” is experiential, it’s a brand promise for escape into a land of childlike wonder; A24 makes no specific promise. There’s really nothing that brings together, say, The Materialists, Everything Everywhere All at Once, and All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt.

And I don’t think a film distributor has ever had brand recognition quite like this before. Miramax certainly forged the path of “studio indies,” starting off as a low-budget indie distributor before merging with Disney, getting into production, and winning Academy Awards. So in a lot of ways A24 follows that same path (minus the Disney acquisition).

But here’s a core distinction: if I ask you who founded Miramax, you’ll think, “Ugh, the Weinstein brothers.” Yeah, so, who founded A24?

The answer is Daniel Katz, David Fenkel, and John Hodges, by the way. But I know that most readers of this don’t know that, and that you don’t really know anything about those three men. You certainly didn’t cringe at their names. You don’t really have much of an opinion about them. You, like me, will likely forget all three names after being finished with this article.

Miramax changed the indie world by making indie producers like Weinstein competitive with big studio executives. Much of its story is fundamentally based on the Weinstein brothers’ personalities and, Harvey especially, their ambitions to be recognized power brokers of movie talent. A24 isn’t known for the personalities of the founders, but as an abstract brand whose logo is a stamp of quality.

But yeah, I have no idea what A24 movie first hit critical mass where enough people said, “A24 did it again.” But the first movie I noticed it was Ex Machina.

This movie gives this list a satisfying symmetry because it started with Alex Garland (see 28 Days Later, above) while looping around Silicon Valley hegemony. One could claim, and the movie tried to make clear, that Ex Machina is the anti-Her, coming just one year later and definitively taking the stance of the anti-humanity of virtualized relationships.

However, just like Her, in order to accept Garland’s criticisms of tech culture, we have to accept the premises of what they’re doing: that the intimacy will be there, and will change us. Ex Machina is less anti-Her than Her for goths. Just as goths never unwound the consumerism of their glam rock counterparts, Ex Machina solidified, rather than subverted, Silicon Valley hegemony.

After the success of Ex Machina, Alex Garland became an A24 house talent, one of their most profitable filmmakers, currently the filmmaker that has pulled their largest budget (with Civil War), and much of what is referred to when people are saying things like “the A24 look” or “A24 aesthetic” derives in part from that film.

A24 brand value may not expand into Disney level, but it’s unlikely to go away for a while and nevertheless has inspired similar endeavors from the likes of Neon and Mubi. Even if A24 one day dies, a fan-supported film distribution brand is now possible and therefore likely to be a path pursued by distributors well into the future.

Before I continue, I have to take a little bit of a diversion. A movie that does not quite fit the ‘influential’ list but should be looked at from the frame of reference of the Her / Ex Machina dynamic is M3gan (2022).

Here is the reason why: all three movies are about our relationship to devices (as opposed to “technology” writ large. Modern consumer implements hooked up to computers). All three of them treat the relationship we have with them as matter-of-fact.

But M3gan just accepts the world it lives in instead of tries to question it in a way that re-enforces it. It’s more matter-of-fact: yeah we’re gonna have childcaring devices, and some of them might go crazy and try to kill us. Haha, oops. In a weird way that makes M3gan more subversive than what either Her or Ex Machina attempt. It doesn’t say “We should consider the implications” but rather “I mean, you already know about this.”

M3gan in fact is following the trajectory of Terminator, where the initial villain in the first movie becomes the body guard in the second movie, and thus in the same way the initial anxiety about weapons tech becomes a debate about its alignment. Terminator is a perfect late 20th Century movie, where liberal artists like James Cameron eventually became the machine they criticized. M3gan is Terminator for Zoomers.

But M3gan isn’t influencing how we tell these stories, it exists because of the influence of movies like Avatar, Her, The Avengers, and Ex Machina.

I also bring M3gan up because where Her was distributed by Warner Bros and Ex Machina was distributed by A24, M3gan was distributed by Blumhouse. And that’s the three modes of mainstream commercial cinema we’re currently living under: studio, studio indie, and genre indie; or: corporate, premium, and populist media. This becomes important for the next section.

Moonlight (2016) / Get Out (2017) / Black Panther (2018) — Black Cinema Competes

In December of 2019 when people were making the “top films of the 2010s” lists, I posted the following the Facebook:

Best movies of the decade go to American black cinema in general.

Get Out, Moonlight, and Sorry to Bother You as luminous examples on the big screen. I really enjoyed Dear White People and BlacKkKlansman despite various criticisms of them.

I may have saw better movies or movies that I liked more, but honestly I currently remember and hope to continue remembering this decade for when cinematographers started saying, "Naw bro, this is how you light black faces."

[As well as] An Oversimplification of Her Beauty, a movie that still excites me years later. If there's any movie I listed you missed, An Oversimplification of Her Beauty is the one I most urge you to see.

The movies I listed were top of mind in 2019, but the movies I list for this section have distinct reasons to be highlighted.

Firstly, they’re not just all directed by black men, but are about black men dealing with black cultural concerns. Before these movies, most black-helmed movies were either comedies about a black man in a dress, directed by Spike Lee, or considered experimental films. There were successful black filmmakers such as John Singleton, but their successes were confined by studio disinterest from breaking out into being the phenomena they probably deserved.

Secondly, these were all visibly successful movies, in other words, phenomenal:

Moonlight won the Academy Award for Best Picture, signifying critical and institutional competitiveness of black-led filmmaking.

Get Out was an instant genre cult classic, grabbing worldwide fans of the genre across demographics regardless of the movie’s base in American black anxiety. It also attracted a lot of critical and new audience acceptance of horror film as a highbrow genre.

Black Panther was a popular, well-respected, and very profitable episode of the MCU and has helped make Ryan Coogler’s actual profitability as a talent for the studios competitive with none other than Steven Spielberg.

Lo and behold: Moonlight was distributed by A24, Get Out by Blumhouse, and Black Panther by Disney. The trifecta of mainstream cinema corporate, premium, and populist media all topped by black-helmed and black-leading talent.

Sinners this year landed this statement in a single movie, what these three movies told any film market observer without denial running through their veins: “black” movies are as good, as profitable, and as audience-friendly as “white” movies. Which they could always have had been, had Hollywood chosen to support more black filmmakers and stories, and given them the same sort of production and marketing support they give white filmmakers.

The denialists in charge of greenlighting and marketing are holding the line on international audiences due to endemic racism. “We’re not racist, it’s just that the Chinese are.” But that wall is crumbling, and good riddance to it.

A little house-cleaning before I go:

These movies are the most influential in how they’ve affected cinema in the 21st century, which does not mean they were the first to do whatever they did that changed things. Indie features were made on HDV before 28 Days Later. Multi-movie contracts were written with filmmakers, particularly directors before Lord of the Rings and Spider-Man. Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004) preceded Avatar in green-screen dominated virtual world digital filmmaking. Serialization was well known before The Avengers. “People might someday want to bone robots” is not a new 21st century concern. Black cinema has existed as long as cinema has.

What makes these movies influential is that they hit a critical mass of acclaim, profitability, audience appeal, pop culture referentiality, and general knowledge and awareness of them. It isn’t that it’s the first time this thing happened, but that it’s the tipping point when that thing became a modality of 21st century filmmaking.

This also sets up these movies to be criticized for being overrated, which, maybe. It doesn’t change their influence, unfortunately. I’m not necessarily recommending them though on par I believe they’re “good” movies.

Some of the above movies inspired me. 28 Days Later was a profound cinematic experience that had me raving (or raging?) for years after and was a regularly-watched DVD that I studied and watched all the special features and director’s commentary for. Lord of the Rings lived up to my most wild fantasy nerd dreams and made it seem like movies could respect magic again. Moonlight I was really excited to see win the Academy Award, which I didn’t feel was possible. Get Out was one of my favorite times spent in a movie theatre and ended up calling me out with my intentions to “see a black movie” as a white person; Jordan Peele got me good and I can do nothing but give him the credit for doing it masterfully.

Most I enjoyed but didn’t personally inspire me, like Avatar, Her, Spider-Man and Ex Machina. And I haven’t even seen Black Panther, so this list was not written entirely with personal appeal in mind.

These are, as I see it, the movies that shaped how cinema is perceived as art and run as a business in the 21st century. More will come, and the industry is always changing, but movies subsequently either live in or are trying desperately to crawl out of these movies’ shadows.

To read my previous film essays:

5 Flicks to Get Cinematically Fit | FilmStack Challenge #3

As this monthly series is taking shape, I’ve had to adjust the name of it. First I titled it Ted Hope’s Challenge, because Ted Hope was the one who wrote the challenge. Then I called it the Hope for Film Challenge because it was bringing in a whole community of his readers. Now it’s squarely the FilmStack Challenge, which nomenclature others got to far ahead of…

Hope for Film Challenge #2: 5 Ways to Improve the Moviegoing Experience

Ted Hope is turning out challenges to “FilmStack” writers at what looks like will be a monthly rate, starting with 5 Tenets for Running a Movie Studio. The second challenge is “5 Ways to Improve the Moviegoing Experience.” I enjoyed my first foray, and of course can pontificate upon nearly any subject about movies, so I’m in.

Ted Hope's Challenge: 5 Tenets for Running a Movie Studio

Ted Hope sent a challenge to various film writers and filmmakers on the platform to write about what five tenets they would follow if they inherited a film studio. In his initial Notes post before the article was published, I commented five things I would do, but I do have to alter them slightly because the actual article specifies:

To watch some of my own movies:

Ominous Horizon

I’m doing something different for my contribution to Soaring Twenties Symposium this month: releasing a short film I’ve been nurturing on the film festival circuit for a year and a half.

Pre|Concept|Ion

Just in time for Easter I bring you this work about spring, new life, and fertility. It’s an ambient, experimental video, so I recommend you watch it with lights off, full screen, and audio turned up.

They That Spoke to Me That Night

This video was produced for the Soaring Twenties Social Club (STSC) Symposium. The STSC is a small, exclusive online speakeasy where a dauntless band of raconteurs, writers, artists, philosophers, flaneurs, musicians, idlers, and bohemians share ideas and companionship. Each month STSC members create something around a set theme. This cycle, the theme was “Dreams.”

Great list, Dane!

This is a really nice breakdown and a refreshing counterpoint to the top 100 - which is nice to absorb, but a bit overwhelming at the moment. Thank you for sharing this !