Two weeks ago I posted Moviegoing Memories, a roundup of personal experiences I’ve had at the cinema that I originally posted to Facebook about four years ago and decided to transfer to Substack.

After I finished the Moviegoing Memories, I proceeded to write some Bookreading Memories over the next couple of weeks. Like the Moviegoing Memories, they’re arranged roughly in chronological order, and are not necessarily the best books I’ve ever read so much as created indelible moments that have stuck with me over the years, for better or worse.

Wherever possible, I have tried to use the cover of the edition I read.

Here they are, with some updates and light editing. If you received this as an email, I recommend clicking through to the webpage or scrolling to the bottom and clicking “view entire message”:

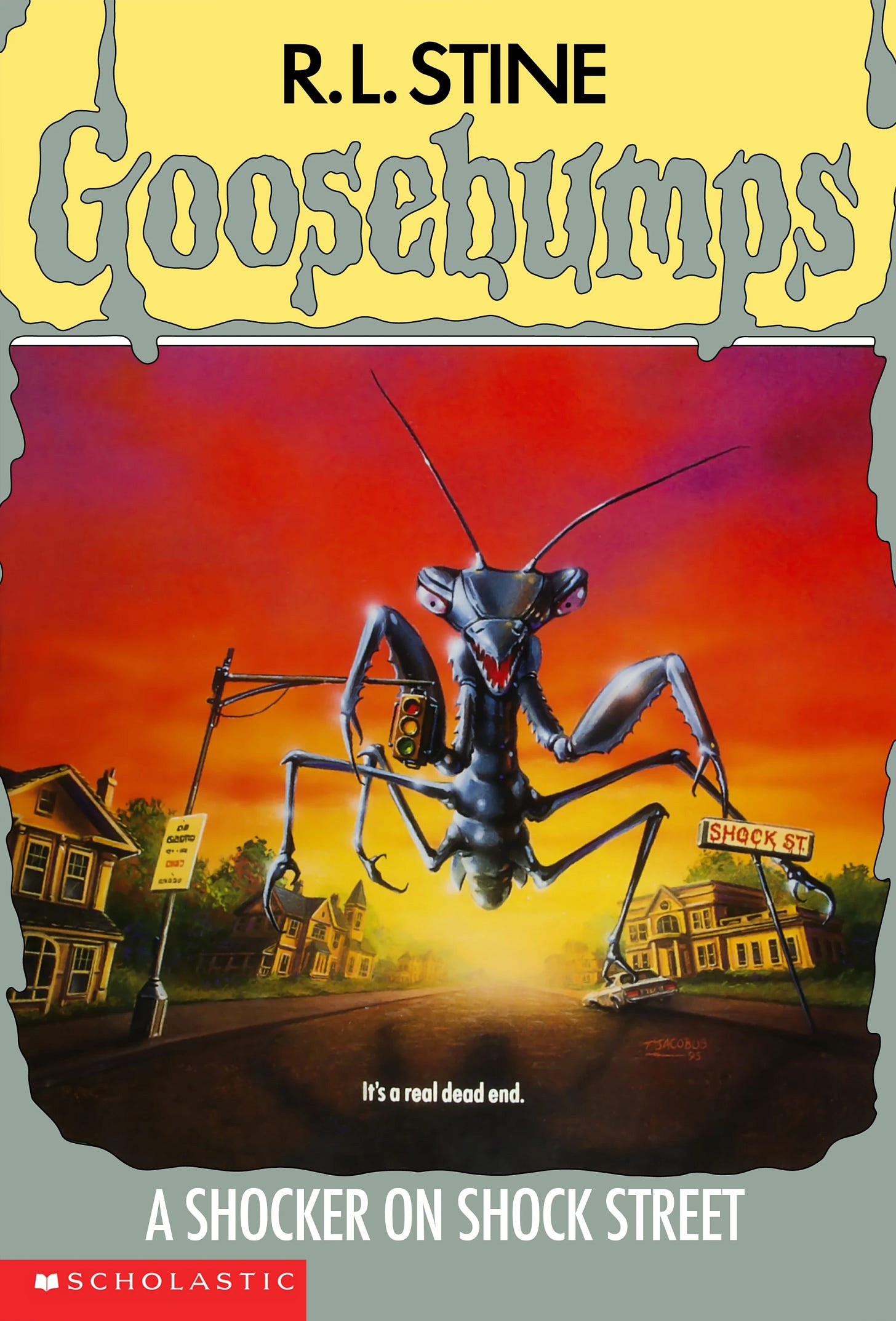

Bookreading Memory #1: Goosebumps

Befitting Facebook meme-culture '90s kids be like' type posting, Goosebumps intersects a lot of memories of what elementary school was like, from heading to the Scholastic Book Fair with a $10 bill and knowing you'll be able to walk away with the new Goosebumps and The Stinky Cheeseman and Other Fairly Stupid Tales, to teachers being big ol' bores and refusing to let Goosebumps be used in book reports.

But regardless the pop culture, there's still a lot of how Goosebumps really influenced me personally. For one thing, Curse of the Mummy's Tomb gave me a deep interest in Ancient Egypt and its mythology, and Night of the Living Dummy has permanently affixed ventriloquist dummies as the coolest, funniest, creepiest, most dangerous motherfucking toys on the planet.

Even the stupid ideas were wild. Vampiric sponges that lived off of people's hate and could only be killed by petting. Green goo that grew, and that was worth writing about three or four times. Kids turning back into the dogs they originally were for some reason.

But there's a lot of these stories that stuck with me in the weird and uncanny that makes horror pleasurable. The very first book was a creepy ghost tale of a strange community that lived in the shadows. One book told of a shapeshifting supervillain that stalked a comic book nerd. And then there's the featured book cover I chose.

Motherfucking A Shocker on Shock Street. Holy god this book. Ostensibly about two kids trial testing an amusement park, everything in this story felt dangerous, creepy, and deliriously surreal, and then the ending happened. I may be just post hoc rewriting my own memories, but considering that this book features unreliable narrators, uncanny valley, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, simulation and simulacra, body horror, and identity subversion, either my deep enjoyment of it foretold my later taste or created it. This book was my first real experience of 'mindbending.' Nothing felt real after I finished it, it’s like the book had reached in and squeezed the juice right out of my brain.

Alls I remember is that, whereas I'd often read a Goosebumps book in a sitting or two, this one I read in one sitting without ever being aware I was reading. Deeply immersive storytelling. That's what Goosebumps could do at its best.

Also, just from a design standpoint, these books gave you something for being books that made the object itself part of the experience. I can't be the only kid who would run my forefinger over the haptic bumps on the the extruded logo while I read, connecting the enjoyment of the story with the tactile quality of the experience. I'd get depressed when the books got old enough that those bumps wore down, so a crisp new Goosebumps book was also a joy.

The publishers were also super genius to put little numbers on the spine, guaranteeing the collectibility of the full series. As an adult I actually actively avoid stuff like that because I'm terribly completist. Stuff like Criterion Collection gives me a bad collector's itch that is great for companies that do it, but bad for my own shelf-space and bank account. Also why I avoid getting in too deep on comic books.

A part of me wants to read Goosebumps again for the lulz, but I know they were written for, like, eight year olds, so I can't expect them to live up to my memories.

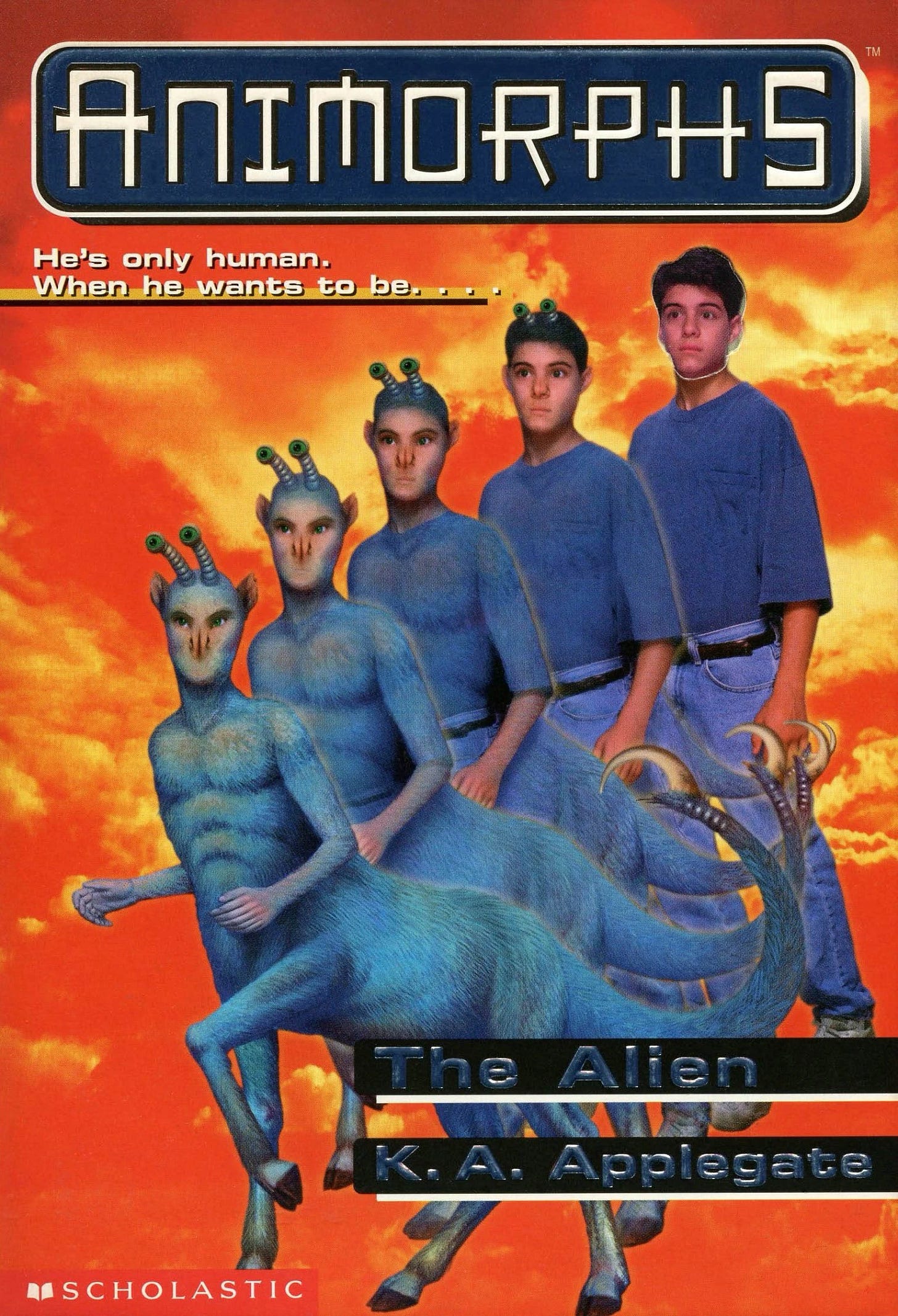

Bookreading Memories #2: Animorphs

Obviously.

Of course this follows Goosebumps, these were the one-two hit of 90s Scholastic book fairs, rolling us right from elementary school into middle school. But unlike Goosebumps, these weren't just fun stories enjoyable to read.

Fear. Anger. Grief. Death. Loss, abandonment, love, trauma, hope, trust. Holy shit this series put you through the feels.

And that's just emotionally: aliens, tech, animism, post-humanism, time travel, interstellar war, domestic resistance, interstellar religions, biology, history, ecology, sociology, evolutionary theory. These books sometimes had me stopping to REALLY IMAGINE what it must be like to experience taste for the first time, or be part of a hive mind, or be stuck in a hawk's body. These books had me researching RNA to figure out how morphing could actually work and deeply questioning the morality of the actions from the characters at others.

At the center of her work, K.A. Applegate has one major, remarkable skill -- the ability to put you in the mind and perspective of 'an other', and question your sense and relationship to reality. These books are about kids with the superpower to turn into animals to fight space slugs, but any time you felt you had a handle on what was what you'd learn the Hork Bajir were peaceful vegans, or Yeerks were capable of love, or maybe children aren't so innocent as we expect.

And how terrifying would it be to be consciously trapped in your own body with absolutely no control of your thoughts or actions? Or how bad does your life have to be to actually consent to that?! There's some terrifying shit in those books.

One time during Banned Books Week, the library hosted an 'open debate' kiosk with essays from various thinkers arguing for or against banning books. One writer on the for banning side derided the argument, "at least it gets kids reading" with the counter-argument, "Reading what? Reading Goosebumps leads to reading Animorphs. It doesn't lead to reading Shakespeare."

To that name-forgotten fuckwad, two things: a) I doubt you were pouring through sonnets at 10 years old, and b) Yes, Goosebumps led to Animorphs. Animorphs lead to Lord of the Rings. Lord of the Rings led to Shakespeare. Or, in my case, the reason I was at the library that day was to check out the third volume of Neal Stephenson's Baroque Cycle, a fucking 3500-page globe-trotting historical epic that uncovers the Early Modern roots of global trade, finance, computer science, and cryptography. Goosebumps leads to Animorphs, Animorphs leads to researching the history of gold trade as it affected both Caribbean pirates and Japanese Samurai. YOU fucking read the Baroque Cycle and tell me what Animorphs leads to. Doubt you could finish the first of six volumes.

Fuck that guy. Animorphs is and will always be legit.

Bookreading Memories #3: IT

Around when I was 11 or 12 I got I really into horror movies, the video store rental classics such as Poltergeist, Pumpkinhead, Village of the Damned, you know the ones. Unlike Goosebumps, this stuff actually scared me, challenged me to sit in my discomfort and try to breathe in and be calm as the rising violins portended something about to leap out and try to kill someone on screen.

I figured, being a reader, if horror movies were really doing it for me I gotta get in on horror literature, so I went to the bookstore and looked to acquire my very first Stephen King novel.

Why IT?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Indulging a Second Look to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.